Expressions of the early youth life in war and embargo (from 1980s to 2010)

In the 1980s, I sat on benches on the three of four feet verandah at Mark master’s house to learn much of my art. Every evening I would cycle hurriedly from Jaffna university, where I followed my under graduate studies on bio-Science to Master’s place. There was an embargo on the North of Sri Lanka, there was very less food, no soap, no fuel, no electricity and many more no’s. Continuous bombing, shelling and internal displaceents became the routine of our lives. We strived our lives through it.

Mark master taught me to express myself through art and that mediums of art are not a hindrance to lose yourself in the magic of lines and colours. He inspired us to express ourselves through art on the streets, in the middle of the ocean and as bombs were continuously falling from the sky. It was a time a war when death and loss had been normalized. The Sri Lankan and Indian armies along with multiple armed groups were all around us.

He taught us to build awareness through our art to live as human beings in the midst of all of this; to live without fear and to ask questions. Apart from teaching art, he provided opportunities for the girls of Jaffna as myself to cross various barriers they would otherwise not be able to cross. This is a significant reason behind my life as a Feminist even today. At a time when there was no point in waiting to gain access to some or the other conventional medium of art, he introduced different mediums amidst us to make art with. These included pieces of wood put aside to sell as firewood; glass and plastic bottles; soap; Styrofoam; cement walls; stone and the list goes on.

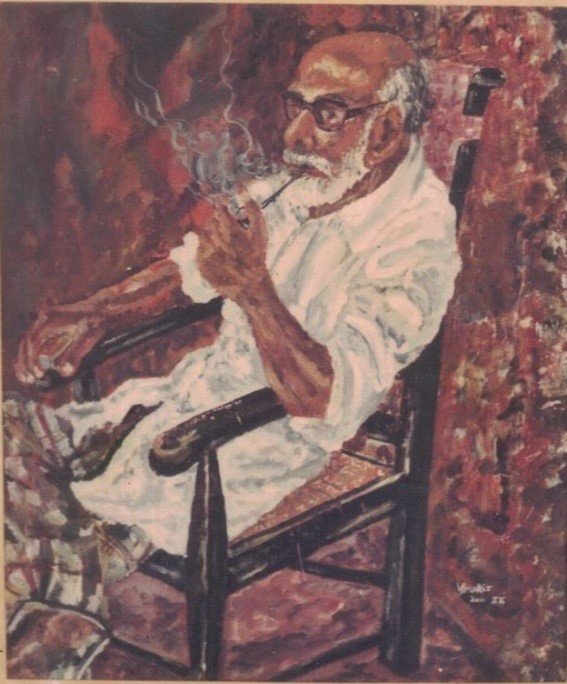

Portraits, Landscapes and still lives

Portrait of Mark Master (A.Mark), emulsion paint, acrylic and other paints on board, 1988

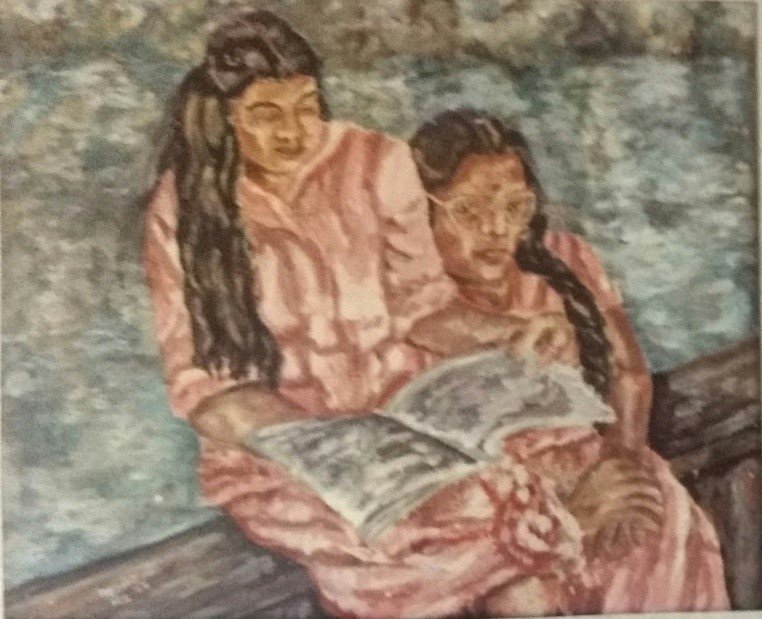

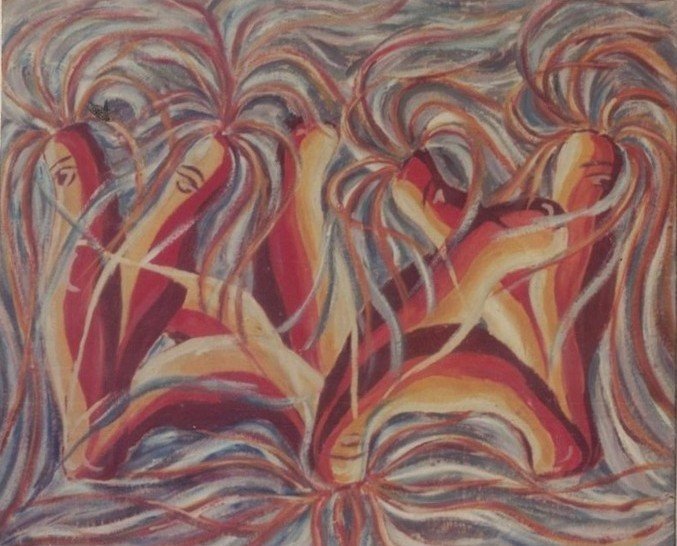

Sisters, Oil on board, 1988

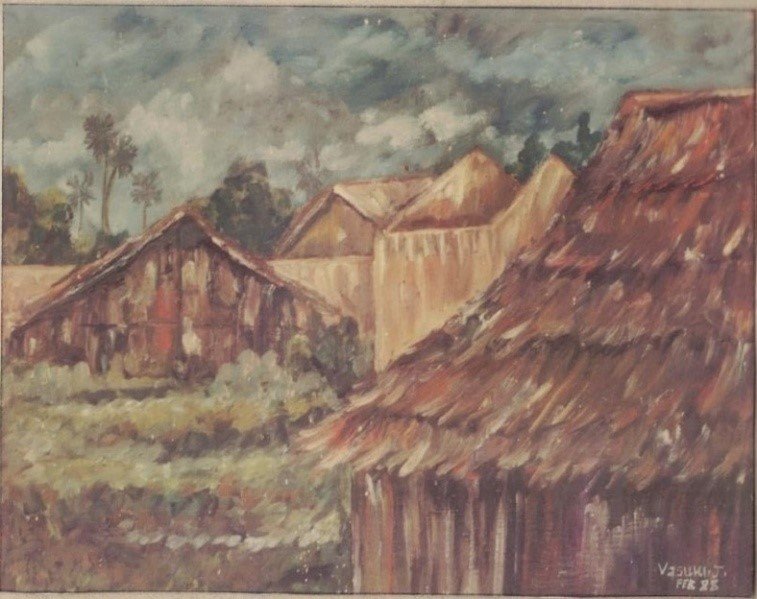

Gurunagar, Oil paint on board, 1988

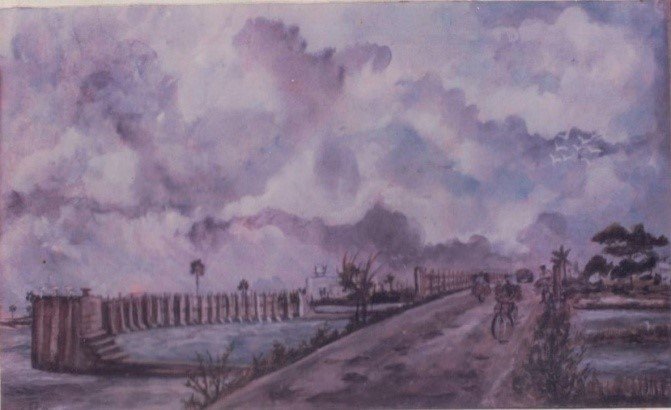

Navatkuli bridge, water colour on Paper

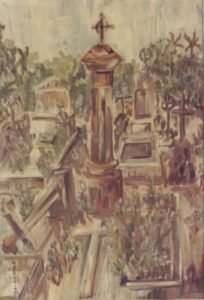

Konchenchi Madha Cemetery, Oil on Board, 1988

From the classroom on Science

I studied science even though I didn’t have much interest in it. The symbols, the nature and its movements would flow in my heart as artforms…together these became paintings.

Locomotion of Hydra, Printing ink on board, 1987

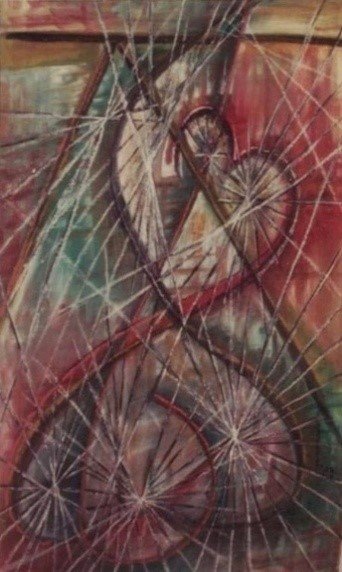

Strive, Oil on board, 1991.jpg

Art as witness to the hatred, war and violence

Art works evolved from the pain and anger of living in oppression, violence and war – to etch our sides of the stories in war, and to give meaning to my/our survival and existence.

Art gave the courage to not to be silent.

Footprints of Death, Mixed media on board, 1987/88

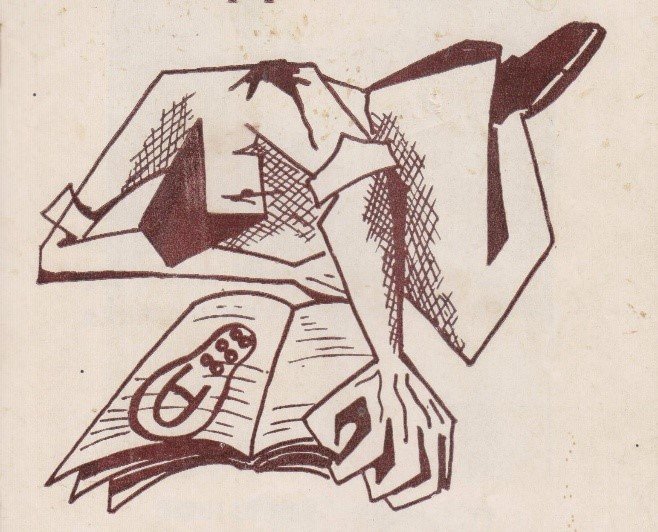

02.02.89, Pen on Paper

The students from Jaffna university did a protest at the Parameshwara junction, blocking the roads, against the round-ups and attacks inside the university by the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). The IPKF came in military tanks and started to attack the peaceful protest of student’s. They were shot, stabbed and beaten. We lost two of our colleagues Satyendra and Jeganathan, and many other students were injured. The books we had to leave behind and run are covered in the shoe prints of the army.

Drawing was made for the cover of a booklet published in remembrance of Satyendra and Jeganathan

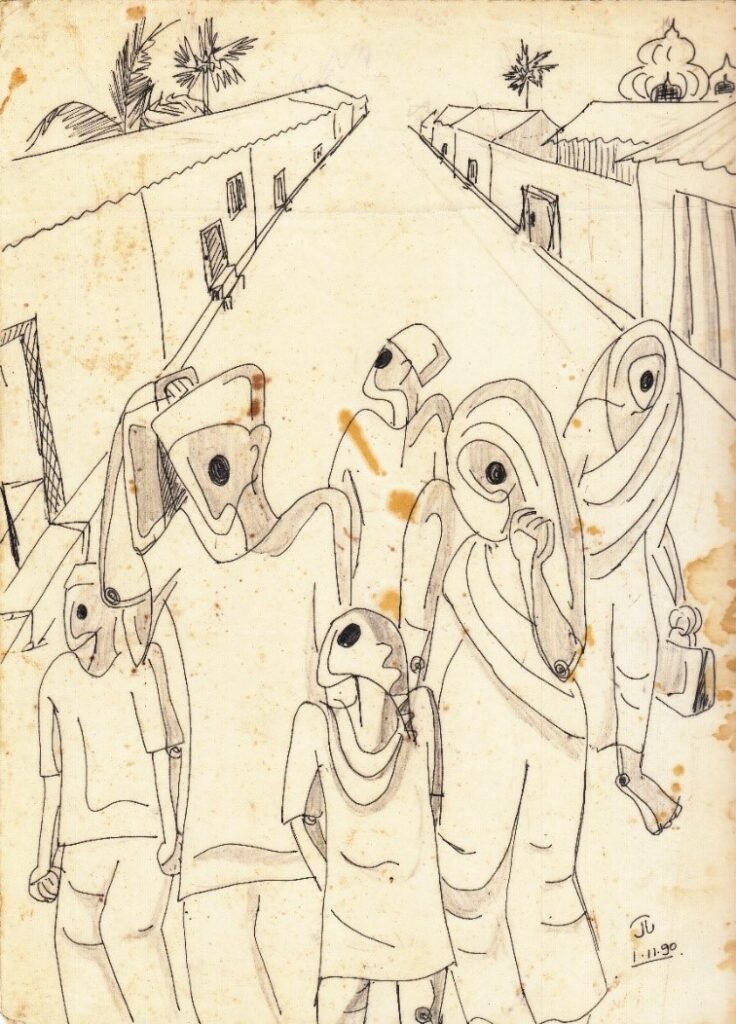

Eviction of Muslims from the north, pen and pencil on paper, 1990

On October 30th, 1990, there was news that all Muslims have been told to leave Jaffna by the LTTE, and that they are moving out by the hordes on Kandy Road. People rushed over with their bicycles to look at the people who were leaving. My father, uncle and others were worrying about what happened to the people they know. For me it was my Maths teacher; Jesima Pictures shop who put lovely frames on pictures and carefully packed it on the carrier of my bicycle; the Tip Top shop keeper who called me a ‘warship’; I remember a whole lot of faces like this. We were helpless and all we could do was just listen to the stories. For me, all I could do is draw a picture.

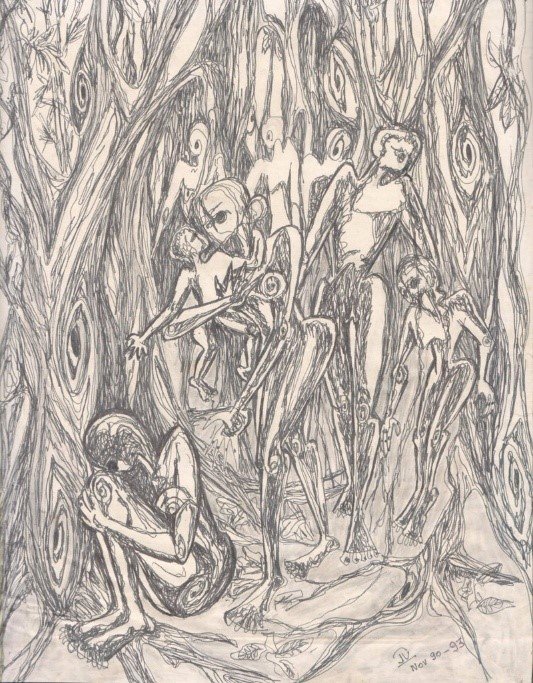

Kokkadicholai, Ballpoint pen and pencil on paper, 1993

After the Indian Peacekeeping Force left, the war restarted between the Sri Lankan Army and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in the 1990s. People in Batticaloa were killed and disappeared in the hundreds. During this time people could not connect much with one another across Jaffna and Batticaloa. All news was either from the Government or the LTTE. In that context, I heard of the massacre in Kokkadicholai. I heard stories of people who ran into the forest in fear, had no food to eat and they had to keep washing and wearing the same set of clothes. At that time, I only had sheets of typing paper and ordinary ball point pens to draw what I felt about this.

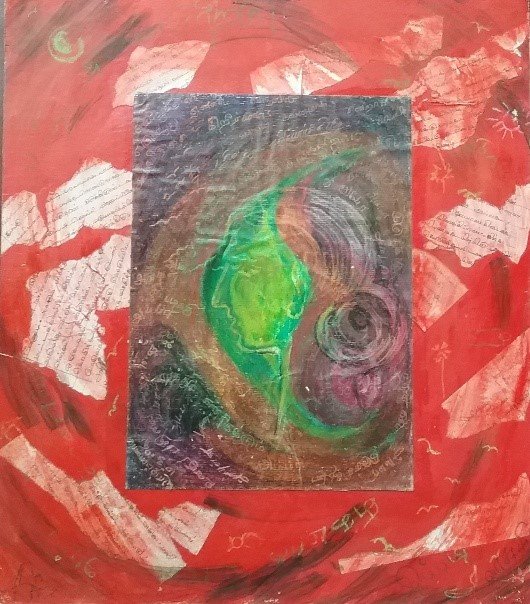

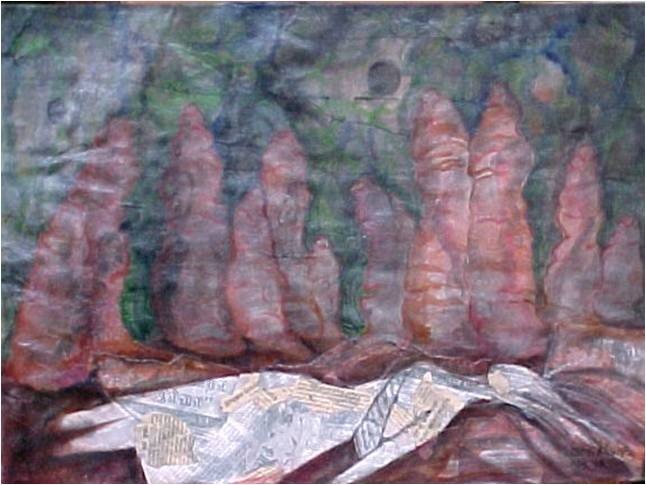

Last letter from mother, Collage with pieces of copied letter, pastel and acrylic on board, 1997

As the army moved in to take over Jaffna on October 30th 1995, the people of the Jaffna peninsula left and moved towards Thenmaratchi in Vanni. I have heard that they walked through rain and muck with all their belongings and drinking the rain water to help with the exhaustion. My mother, father and brother walked this way via the Navarkuli bridge to leave the peninsula. I had already moved to Batticaloa by then. My family stayed in Manduvil in Thenmaratchi, at a relative’s house with twenty-five other people. Walking through the rain and living without basic facilities after enduring displacement was making my mother’s Asthma worse. The letters she wrote to me would take months to somehow reach me in Batticaloa. People in the war zone sent letters through those going to Colombo or they used the post offices set up at the refugee camps. Slowly letters would make their way from the LTTE controlled areas to the Army controlled areas and from there through ocean routes or land routes, after many weeks, the they reached their destination.

In March, 1996 someone from the Bank of Ceylon in Batticaloa dropped off a small piece of paper. My father, who was a retired employee of the bank sent news through employees at the makeshift bank set up in the Manduvil refugee camp, to get this note to the Batticaloa branch. This piece of paper said that my mother had passed away.

Two, three weeks after this, I got a letter in the post. It was a letter that my mother wrote to me before she died. This is that letter…

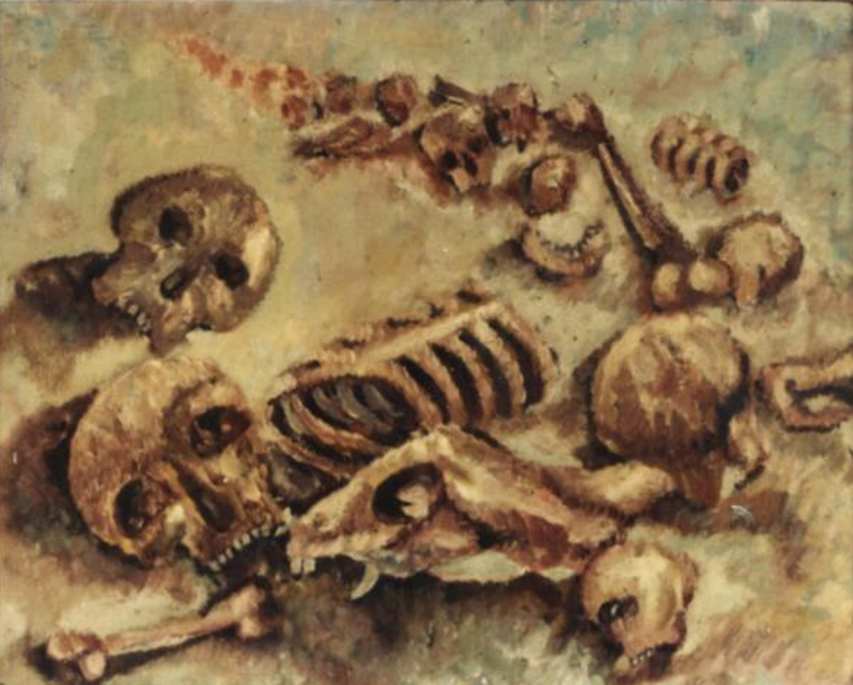

In Search of the buried, Water Colour on paper, 1997

People are being disappeared continuously… the war in the north and east and the JVP insurrection in the south… no side of these conflicts have respect for human emotions or lives…Women face the horrid plight of having to dig in the ground looking for those disappeared who may be buried…Suriyakantha, Semmani, Sathrukondan… the list continues…

Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, Water colour, pieces of newspapers on hard board, 1998

In 1996, Krishanthi Kumaraswamy who was returning home after her A level exam was arrested by those in the army camp on the way. Six army personnel gang raped and killed her. They killed her mother, brother and neighbour who went in search of her and buried them all in Semmani. All that was left was what was reported in the newspapers as being that young woman’s dreams.

The artwork is done with collaging the news paper cuttings about the incident, protests and legal case.

Binthunuweva, Colour pencil on paper, 2002

Binthunuweva is a State’s rehabilitation Centre for suspected child soldiers of LTTE. This place was attacked by a mob (said to be from the surrounding villages), many kids were killed and burned.

In Batticaloa town, there was a bomb blast followed by a shooting on the day of Vesak in the year 2000. Many were killed in this violence, including children. But people found themselves unable to even say that they saw or heard this violence. They were forced to keep quiet.

Vesak 2000, mixed media on board, 2000

Vesak 2000, mixed media on board, 2000

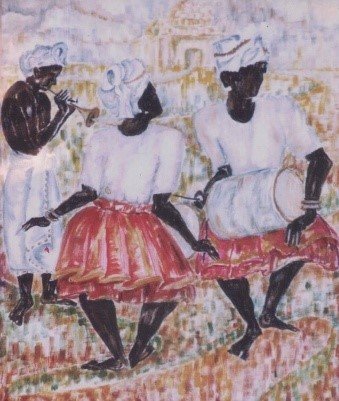

Parai drum is a traditional drum for us. I respect the artists who play the drum. If the parai was to be taken out of the temple and other new instruments are introduced in its place, the Gods who took pleasure in the parai beats will also come out of the temple and dance with the drum.

Pillaiyar who broke off his tusk to write the Mahabharatha will use the same tusk to play the drum. He will play the parai…

My child is not for war

My child is not for war, Oil pastel on Paper, 1996

My child is not for war, Oil paint on board, 1998

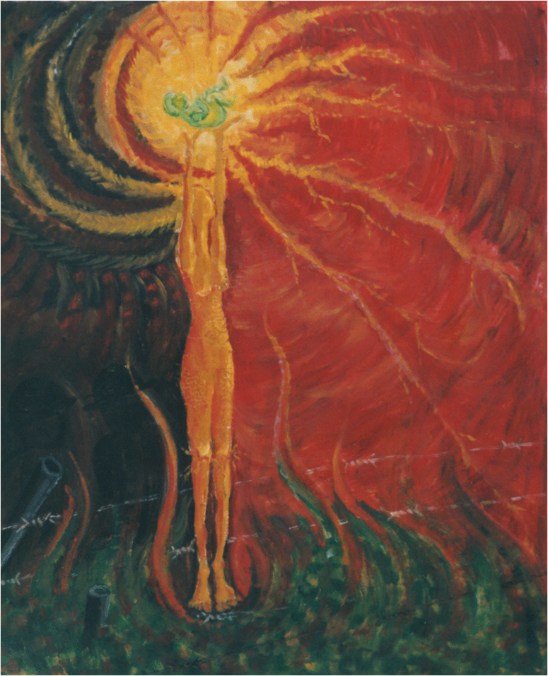

Birth is like a lotus blossoming. This painting asks the question of whether children and nature are only to be born in a securitized world.

My child is not for war, Oil paint on board, 2003

Who has the right to kill women’s children?

Who has the right to turn women’s children violent?

How is it fair that the children that women give birth to after such agony are given different ethnicities, religions or some other identity and are disappeared or killed because of that?

The decision of whether a child should take up arms is being taken not by the mother but by all sorts of other people. Various people are selling and buying weapons that kill the children…

While working in women’s rights and child rights organisations during the war, these are the questions and agony I was left with from listening to endless stories of women who lost their children

There must be a land with no violence where children from mother’s wombs can be born into. Without that mothers must take a pledge that they will not birth children to be killed by somebody or to kill anybody. I take this pledge.

Come together to grant a boon

Oh people of the world

Come together to grant a boon

Grant a boon for

My child whose weight I bear in my dreams and my thoughts

My child whose weight I bear at the core of my being as a penance

Grant a boon for that child to be born

My child that

Cannot be killed by bombs of weapons

Or by the anger of a brother

Or that of nature

My child that has gotten the boon of

Not dying from anything

My foolish child

Who doesn’t sell the wind

Or water

Or make weapons that split the earth in two

Or doesn’t know to have acid rain

Come down upon the soft grass on which the child learnt to walk

Grant me a boon for this foolish child to be born.

If it isn’t born today, it may never be born

So let us come together to birth this human baby